RosettaNet is a non-profit consortium aimed at establishing standard processes for the sharing of businessinformation (B2B). RosettaNet is a consortium of major Computer and Consumer Electronics, Electronic Components, Semiconductor Manufacturing, Telecommunications and Logistics companies working to create and implement industry-wide, open e-business process standards.[1] These standards form a common e-business language, aligning processes between supply chain partners on a global basis.[2]

RosettaNet is a subsidiary of GS1 US, formerly the Uniform Code Council, Inc. (UCC). It was formed mainly through the efforts of Fadi Chehade,[3] its first CEO. RosettaNet's 500 members come from companies around the world. The consortium has a presence in USA, Malaysia, Europe, Japan, Taiwan, China, Singapore, Thailand and Australia.

Jan 15, 2021 Rosetta 2 enables a Mac with Apple silicon to use apps built for a Mac with an Intel processor. If you have a Mac with Apple silicon, you might be asked to install Rosetta in order to open an app. Click Install, then enter your user name and password to allow installation to proceed. The Rosetta software suite includes algorithms for computational modeling and analysis of protein structures. It has enabled notable scientific advances in computational biology, including de novo protein design, enzyme design, ligand docking, and structure prediction of biological macromolecules and macromolecular complexes.

RosettaNet has several local user groups. The European User Group is called EDIFICE.

The RosettaNet Standards website shut down by the end of 2013 and RosettaNet Standards is now managed as part of GS1 US website.

The RosettaNet standard[edit]

The RosettaNet standard defines both e-commerce document and exchange protocols, as part of the Electronic data interchange (EDI).

The RosettaNet standard is based on XML and defines message guidelines, interfaces for business processes, and implementation frameworks for interactions between companies. Mostly addressed is the supply chain area, but also manufacturing, product and material data and service processes are in scope.

The standard is widely spread in the global semiconductor industry, but also in electronic components, consumer electronics, telecommunication and logistics. RosettaNet originated in the USA and is widely used there, but it is also well accepted and even supported by governments in Asia. Due to the widespread use of EDIFACT in Europe, RosettaNet is used less, but it is growing.[citation needed]

The RosettaNet Automated Enablement standard (RAE) uses the Office Open XML document standard.[4]

The RosettaNet Technical Dictionary (RNTD) is the reference model for the classification and characterization of the products in the supply chains that use RosettaNet for their interactions.[5]

Industrial products and services categorization standards[edit]

- RosettaNet

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^Adams, Susie; Hardas, Dilip; Iossein, Aktar & Kaiman, Charles (2002). BizTalk Unleashed. Indianapolis, Indiana: Sams Publishing. p. 966. ISBN978-0-672-32176-4.

- ^Boh, W. F; C. Soh; S. Yeo (2007). 'Standards development and diffusion: a case study of RosettaNet'. Communications of the ACM. 50 (12): 57–62. doi:10.1145/1323688.1323695.

- ^Jesdanun, Anick (23 June 2012). 'Internet group picks little-known executive as CEO'. The Austin Statesman. Austin, Texas. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012.CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^an international open document standard called ECMA Open XMLLin, Woon Wu (June 2007). 'RosettaNet Malaysia introduces new biz standard for local SMIs'. Archived from the original on 25 October 2007.CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^RosettaNet (12 September 2007). 'Purpose'. RosettaNet.

External links[edit]

Everything you ever wanted to know about the Rosetta Stone

You've probably heard of the Rosetta Stone. It's one of the most famous objects in the British Museum, but what actually is it? Take a closer look...

What is the Rosetta Stone?

The Rosetta Stone is one of the most famous objects in the British Museum. But what is it?

The Rosetta Stone and a reconstruction of how it would have originally looked. Illustration by Claire Thorne.

The Stone is a broken part of a bigger stone slab. It has a message carved into it, written in three types of writing (called scripts). It was an important clue that helped experts learn to read Egyptian hieroglyphs (a writing system that used pictures as signs).

Why is it important?

The writing on the Stone is an official message, called a decree, about the king (Ptolemy V, r. 204–181 BC). The decree was copied on to large stone slabs called stelae, which were put in every temple in Egypt. It says that the priests of a temple in Memphis (in Egypt) supported the king. The Rosetta Stone is one of these copies, so not particularly important in its own right.

The important thing for us is that the decree is inscribed three times, in hieroglyphs (suitable for a priestly decree), Demotic (the native Egyptian script used for daily purposes, meaning ‘language of the people'), and Ancient Greek (the language of the administration – the rulers of Egypt at this point were Greco-Macedonian after Alexander the Great's conquest).

The Rosetta Stone was found broken and incomplete. It features 14 lines of hieroglyphic script:

Detail of the hieroglyphs, including a cartouche featuring the name Ptolemy (written right to left, along with an Egyptian honorific).

32 lines in Demotic:

and 53 lines of Ancient Greek:

Detail of the Ancient Greek section. You can make out the name Ptolemy as ΠΤΟΛΕΜΑΙΟΣ.

The importance of this to Egyptology is immense. When it was discovered, nobody knew how to read ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. Because the inscriptions say the same thing in three different scripts, and scholars could still read Ancient Greek, the Rosetta Stone became a valuable key to deciphering the hieroglyphs.

When was it found?

Napoleon Bonapartecampaigned in Egypt from 1798 to 1801, with the intention of dominating the East Mediterranean and threatening the British hold on India. Although accounts of the Stone's discovery in July 1799 are now rather vague, the story most generally accepted is that it was found by accident by soldiers in Napoleon's army. They discovered the Rosetta Stone on 15 July 1799 while digging the foundations of an addition to a fort near the town of Rashid (Rosetta) in the Nile Delta. It had apparently been built into a very old wall. The officer in charge, Pierre-François Bouchard (1771–1822), realised the importance of the discovery.

The city of Rosetta around the time the Rosetta Stone was found. Hand-coloured aquatint etching by Thomas Milton (after Luigi Mayer), 1801–1803.

On Napoleon's defeat, the stone became the property of the British under the terms of the Treaty of Alexandria (1801) along with other antiquities that the French had found. The stone was shipped to England and arrived in Portsmouth in February 1802.

Who cracked the code?

Soon after the end of the 4th century AD, when hieroglyphs had gone out of use, the knowledge of how to read and write them disappeared. In the early years of the 19th century, scholars were able to use the Greek inscription on this stone as the key to decipher them. Thomas Young (1773–1829), an English physicist, was the first to show that some of the hieroglyphs on the Rosetta Stone wrote the sounds of a royal name, that of Ptolemy.

A letter from Thomas Young about hieroglyphs, written on 10 February 1818. The meanings he suggests for these groups are mostly correct, but he was unable to analyse how the signs conveyed their meaning, and they are little more than highly educated guesses!

The French scholar Jean-François Champollion (1790–1832) then realised that hieroglyphs recorded the sound of the Egyptian language. This laid the foundations of our knowledge of ancient Egyptian language and culture. Champollion made a crucial step in understanding ancient Egyptian writing when he pieced together the hieroglyphs that were used to write the names of non-Egyptian rulers. He announced his discovery, which had been based on analysis of the Rosetta Stone and other texts, in a paper at the Academie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres at Paris on Friday 27 September 1822. The audience included his English rival Thomas Young, who was also trying to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Champollion inscribed this copy of the published paper with alphabetic hieroglyphs meaning ‘à mon ami Dubois' (‘to my friend Dubois'). Champollion made a second crucial breakthrough in 1824, realising that the alphabetic signs were used not only for foreign names, but also for the Egyptian language and names. Together with his knowledge of the Coptic language, which derived from ancient Egyptian, this allowed him to begin reading hieroglyphic inscriptions fully.

What is the Rosetta Stone?

The Rosetta Stone is one of the most famous objects in the British Museum. But what is it?

The Rosetta Stone and a reconstruction of how it would have originally looked. Illustration by Claire Thorne.

The Stone is a broken part of a bigger stone slab. It has a message carved into it, written in three types of writing (called scripts). It was an important clue that helped experts learn to read Egyptian hieroglyphs (a writing system that used pictures as signs).

Why is it important?

The writing on the Stone is an official message, called a decree, about the king (Ptolemy V, r. 204–181 BC). The decree was copied on to large stone slabs called stelae, which were put in every temple in Egypt. It says that the priests of a temple in Memphis (in Egypt) supported the king. The Rosetta Stone is one of these copies, so not particularly important in its own right.

The important thing for us is that the decree is inscribed three times, in hieroglyphs (suitable for a priestly decree), Demotic (the native Egyptian script used for daily purposes, meaning ‘language of the people'), and Ancient Greek (the language of the administration – the rulers of Egypt at this point were Greco-Macedonian after Alexander the Great's conquest).

The Rosetta Stone was found broken and incomplete. It features 14 lines of hieroglyphic script:

Detail of the hieroglyphs, including a cartouche featuring the name Ptolemy (written right to left, along with an Egyptian honorific).

32 lines in Demotic:

and 53 lines of Ancient Greek:

Detail of the Ancient Greek section. You can make out the name Ptolemy as ΠΤΟΛΕΜΑΙΟΣ.

The importance of this to Egyptology is immense. When it was discovered, nobody knew how to read ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. Because the inscriptions say the same thing in three different scripts, and scholars could still read Ancient Greek, the Rosetta Stone became a valuable key to deciphering the hieroglyphs.

When was it found?

Napoleon Bonapartecampaigned in Egypt from 1798 to 1801, with the intention of dominating the East Mediterranean and threatening the British hold on India. Although accounts of the Stone's discovery in July 1799 are now rather vague, the story most generally accepted is that it was found by accident by soldiers in Napoleon's army. They discovered the Rosetta Stone on 15 July 1799 while digging the foundations of an addition to a fort near the town of Rashid (Rosetta) in the Nile Delta. It had apparently been built into a very old wall. The officer in charge, Pierre-François Bouchard (1771–1822), realised the importance of the discovery.

The city of Rosetta around the time the Rosetta Stone was found. Hand-coloured aquatint etching by Thomas Milton (after Luigi Mayer), 1801–1803.

On Napoleon's defeat, the stone became the property of the British under the terms of the Treaty of Alexandria (1801) along with other antiquities that the French had found. The stone was shipped to England and arrived in Portsmouth in February 1802.

Who cracked the code?

Soon after the end of the 4th century AD, when hieroglyphs had gone out of use, the knowledge of how to read and write them disappeared. In the early years of the 19th century, scholars were able to use the Greek inscription on this stone as the key to decipher them. Thomas Young (1773–1829), an English physicist, was the first to show that some of the hieroglyphs on the Rosetta Stone wrote the sounds of a royal name, that of Ptolemy.

A letter from Thomas Young about hieroglyphs, written on 10 February 1818. The meanings he suggests for these groups are mostly correct, but he was unable to analyse how the signs conveyed their meaning, and they are little more than highly educated guesses!

The French scholar Jean-François Champollion (1790–1832) then realised that hieroglyphs recorded the sound of the Egyptian language. This laid the foundations of our knowledge of ancient Egyptian language and culture. Champollion made a crucial step in understanding ancient Egyptian writing when he pieced together the hieroglyphs that were used to write the names of non-Egyptian rulers. He announced his discovery, which had been based on analysis of the Rosetta Stone and other texts, in a paper at the Academie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres at Paris on Friday 27 September 1822. The audience included his English rival Thomas Young, who was also trying to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Champollion inscribed this copy of the published paper with alphabetic hieroglyphs meaning ‘à mon ami Dubois' (‘to my friend Dubois'). Champollion made a second crucial breakthrough in 1824, realising that the alphabetic signs were used not only for foreign names, but also for the Egyptian language and names. Together with his knowledge of the Coptic language, which derived from ancient Egyptian, this allowed him to begin reading hieroglyphic inscriptions fully.

What does the inscription actually say?

The inscription on the Rosetta Stone is a decree passed by a council of priests. It is one of a series that affirm the royal cult of the 13-year-old Ptolemy V on the first anniversary of his coronation (in 196 BC). You can read the full translation here.

According to the inscription on the Stone, an identical copy of the declaration was to be placed in every sizeable temple across Egypt. Whether this happened is unknown, but copies of the same bilingual, three-script decree have now been found and can be seen in other museums. The Rosetta Stone is thus one of many mass-produced stelae designed to widely disseminate an agreement issued by a council of priests in 196 BC. In fact, the text on the Stone is a copy of a prototype that was composed about a century earlier in the 3rd century BC. Only the date and the names were changed!

Where is it now?

After the Stone was shipped to England in February 1802, it was presented to the British Museum by George III in July of that year. The Rosetta Stone and other sculptures were placed in temporary structures in the Museum grounds because the floors were not strong enough to bear their weight! After a plea to Parliament for funds, the Trustees began building a new gallery to house these acquisitions.

The Rosetta Stone on display in Room 4.

The Rosetta Stone has been on display in the British Museum since 1802, with only one break. Towards the end of the First World War, in 1917, when the Museum was concerned about heavy bombing in London, they moved it to safety along with other, portable, ‘important' objects. The iconic object spent the next two years in a station on the Postal Tube Railway 50 feet below the ground at Holborn.

Today, you can see the Rosetta Stone in Room 4 (the Egyptian Sculpture Gallery), and remotely visit it on Google Street View. You can touch a replica of it in Room 1 (the Enlightenment Gallery). You can even explore it in 3D with this scan:

If you don't have the patience of an early Egyptologist, you can watch YouTuber Tom Scott on how the secret of hieroglyphs were deciphered:

Can't get enough of the Rosetta Stone? You're in luck. Our shop range features everything from memory sticks and umbrellas to ties and mugs!

You can even take home a replica of this iconic object.

Want more Rosetta Stone facts? Take a look at Curator Ilona Regulski's blog, where she shares her experience of becoming the latest custodian of the Rosetta Stone.

Find out more in this BBC podcast about the Rosetta Stone.

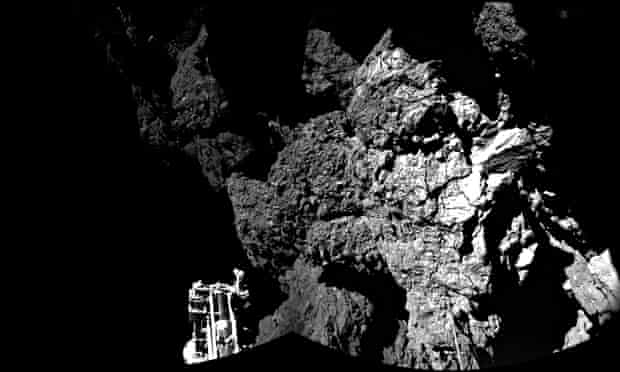

Rosetta Philae Comet Landing

Rosetta & Philae Mac Os 11

Top 10 historical board games

26 February 2021

Read story

Disability and the British Museum collection

3 December 2020

Read story

Rosetta Lenoire

Depicting the dead: ancient Egyptian mummy portraits

27 October 2020

Read story